VOL XXV, No 1 []

Where Did He Put the Pen of My Aunt? Navajo Revealed

David C. Cates, Maplewood, New Jersey

Intricate miracles underlie even ordinary events like sunshine, eyesight, and air. Yet their ordinariness seems to stifle the kindling of wonder. This may be the point of a Zennish riddle that lit my screen from an anonymous comic djinn of cyberspace: “Life has its costs and burdens, but it does include free rides around the sun.” Unlike tornados and eclipses, common marvels just aren’t salient enough to penetrate the stress of dailiness. And high among these simple wonders is language: not the elitist niceties academies fuss over, but speech as it arises from the unruly urgencies of life, double negatives and all.

The nature of language is most strikingly revealed when we open ourselves to one culturally remote from our own, the more so the better. As we learn its forms and idioms, we enter a living museum of vanished millennia, forgetting our first impression: impassive gutturals of wary people whose clothing is often fastened with safety pins.

For such enlightenment to occur, we can ease the initial difficulty by selecting a language that’s accessible, culturally intact, thoroughly described and widely taught. There is no doubt that Navajo, at least for Americans, is that language. Its remoteness credentials, moreover, are impressive. Navajo is one of the Athabascan family of Amerindian languages, a newcomer whose diaspora stretches 7,000 years and 4,000 miles from its sub-Arctic beachhead to northern Mexico. And the dialects of Apache, close cousins to Navajo, let us watch linguistic drift across a mere 500 years of separation. Finally, the entirety of “Apachean” grammar and nearly all its lexicon evolved before the 1500s.1

Accessibility. Among remote languages, Navajo is logistically convenient. First, it’s a lot cheaper to fly to Phoenix and rent a car than to trek to Port Moresby and scare up a bush pilot with guide. Second, Navajo people are known for sprightly wit, practical jokes, and pantomime2, as well as a frequent willingness to converse, explain, guide, and instruct. Third, there is an abundance of language courses, my favorite title being “Navajo Made Easier.” Finally, locating Navajo within Athabascan history—Apache short-term, subarctic cousins long-term—not only deepens our understanding of word origins but recalls the tracing of Indo-European back to its own knowable roots.3

Intactness. Never quite controlled by the Spanish, Navajos were raiders (and raidees) of Utes, Apaches, Hopis, and Mexicans until their defeat in 1863 by troops under the command of Colonel Kit Carson, followed by a 300-mile winter march to southern New Mexico. This traumatic exile came to an end with the 1868 visit of General William T. Sherman. Sent to persuade the Navajos to settle in Oklahoma Territory with the Cherokee and other displaced tribes, he finally let them (now reduced to about 8,000) return to their Land of Emergence, where each family would receive tools, food, and schooling. Navajo population and tribal wealth have risen since, despite the toll of alcohol and drugs.

Scholarship. It was only in the 1930s that a complete description of Navajo was undertaken, directed by the anthropological linguist Edward Sapir. That precedent-setting work—which ranks with the periodic table of Mendeleev—was partially codified in a series of articles (1945–49) entitled “The Apachean Verb,” published in the International Journal of American Linguistics (“American” here means the first ones). No other preliterate culture has been the subject of such academic firepower! A typical Navajo household of the 1930s was said to consist of a grandmother, her four daughters, three husbands (less the one who couldn’t abide mother-in-law tyranny), eight children, fifteen sheep, four goats, and 0.3 anthropologists.

I like to think that Sapir is to Navajo as Chapman was to Homer. Then where was our Keats, our “watcher of the skies” invoking “new plane,” “wild surmise,” and Navajo as elegant human construct? But Romantic ardor is quickly cooled by sentences like this: “With stems whose perfective variant is reduced and ends in an originally glottalized obstruent, the momentaneous imperfective-optative stem should be low-toned in Navajo.”

To be sure, instruction in Navajo thrives in the Southwest, but is altogether utilitarian, directed to health care workers (“Where does it hurt?”), administrators (“This permit has expired!”), storekeepers (“You’ve exceeded your credit limit!”), local school teachers and even missionaries (whose zeal must surely be tempered once they grasp the profound incompatibility of Christian and Navajo belief).

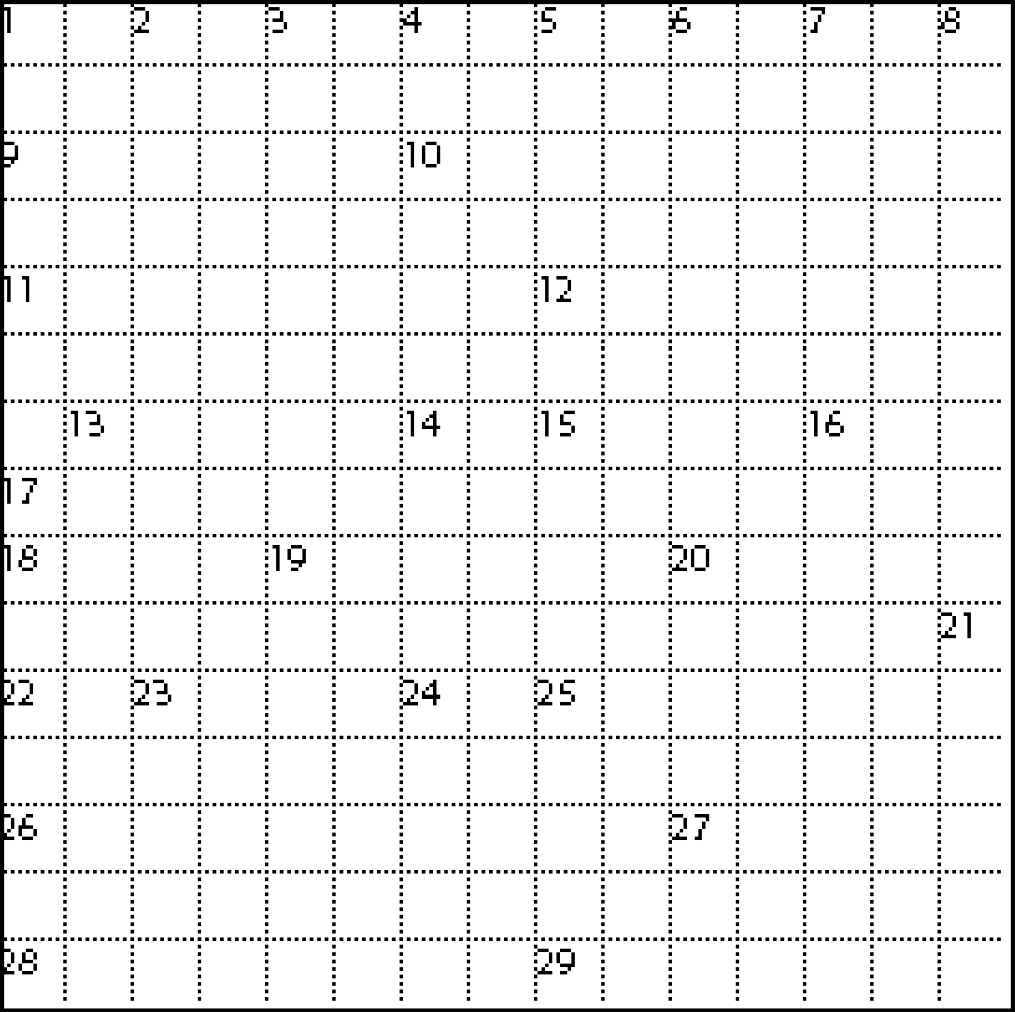

The phrase “Where did he put the pen of my aunt?”, based on that famous French classroom query, seems absurdly culture-bound. Yet the parsing of this simple question lets us dive through the looking-glass into seven distinct Navajo wonderlands:

Looking-glass Wonderland

“where” A vast and precise lexicon for location/direction

“?” Forming a question

“did”The treatment of tense and aspect

“he”The curious simplicity of Navajo pronouns

“put” Verbs for the handling of different kinds of things

“pen”The naming of non-native artifacts

“aunt” Kinship terminology

1. Location/direction. The eminent anthropologist Clyde Kluckhohn learned Navajo as a teenager when sent by his Michigan family to Ramah, New Mexico, for the relief of asthma. As a teacher, he liked to say that the language was shaped across thousands of years by small groups living close to starvation in trackless land. It was important to be accurate about landmarks, direction, and the ways of coming and going. Compared to English, Navajo is an organized riot of detail on the characteristics of space and its traversing.

2. Questioning. Navajo is a tone language. Thus an end-of-sentence interrogatory high tone, as in “Did you go?” won’t work, since each Navajo syllable already has an unalterable pitch. Nor will inversion work (“did you?” vs. “you did”), because in Navajo these elements are prefixes already tightly ordered into the verb construction. Instead, questions are formed with an interrogative suffix, or—more politely—with an uncertainty suffix, as in “Perhaps you forgot to hobble the horses?”

3. Tense and aspect. The verb has a chassis similar to the Latin verb, in that a final stem is modified by prefixes! But a Navajo verb under full sail (with prefix spinnakers and mizzen suffixes) also does the work of English pronouns, adjectives, adverbs and prepositions. Different modes of action, such as “completed,” “ongoing,” “repetitive,” and “hortatory,” are signalled by phonetic variations of the stem. As for tense (the signalling of “past,” “present” or “future”), this may be implied simply by one’s choice of completed or ongoing mode. Yet certain prefixes and suffixes can override these implications. Thus completed action may be placed in the future, and ongoing action in the past.

“A Vocabulary of Colloquial Navajo,” by Young and Morgan (1951), contains one for Dilbert-lovers: “to serve/file/send a paper” is “to toss [a round object] up.” The round-object stem here refers to the contents, not to the paper itself, which would require a “hide-like object” stem. The dictionary has no entry for our word “love,” because its semantic range is too messy. Navajos distinguish between “Love your hat!” “Love you, baby!” and a unique awareness in which beauty, peace, harmony, and blessing combine to make a single word. To illustrate, the best way to say “I love you” is “through you—with me—there is beauty, peace, harmony, and blessing.”

4. Simplicity of pronouns. The historical remoteness of Navajo guarantees that we will encounter provocative strangeness of concept and linguistic form. Just as amazing, however, is the presence of very familiar elements. Coming to us from high atop the post–glacial stone age, in other words, are nouns, pronouns, direct and indirect objects, active and passive voice, and clearly articulated modes of action and tenses, along with other tried and true structure elements. It’s as though language evolves to frame a universal set of questions, including “Who, what, where, when, how, and why?”, that discipline of journalism. Why shouldn’t a parallel invention of the framing devices also occur?

The Navajo pronoun system is more truncated than English’s, in two ways. First, third person singular is a monosyllable standing for “he,” “she,” or “it,” depending on context. But there is a third person honorific for, say, one’s grandfather, Coyote, Bear, and always in the verb standing for Sun (‘respected round object rising’). Second, the pronoun for “we” and plural “you” is one and the same. Context can sort out the difference, but the clues can be hard for a novice to find.

Did the politics of matriarchy lead to the genderless pronoun? I have another theory. With its multiple prefixes (many pronoun-possessed), the Navajo verb system is already stretched to capacity. If it is to be learned by children, low-wattage adults, and even missionaries, complexity has to be rationed. This seems to explain both simplifications.

5. Object-specific verbs. Some of our “handling” verbs are specific to what’s handled (try saying, “Pour me the newspaper”), but verbs like “put” can be applied to almost any object. Navajo speakers, by contrast, must use ancient stems, each appropriate to a general class of things, whether a round object, a flexible, rope-like thing, scattered objects, loose granular matter, liquid in a container, etc. If you use the wrong stem (say, “round object” for “arrow”), Navajos will snicker helplessly. The stem for “pen”? “Arrow-like thing.”

6. Naming artifacts. The proud and skeptical Navajo spirit has led speakers to invent their own words for things of American make. “Wagon,” for example, is rendered by a construction whose semantic elements are: “wood—here-and-there—rolls.” “Telephone” is rendered as “metal—talks.” The construction for “pen” is a verb, whose literal translation is: “by-means-of-it—on-its-surface—there’s scratching.”

The terminology for auto parts is based on old pan-Athabascan nouns. The car—first chugging into Navajo country around 1910—was seen as a horse, albeit mechanical. Thus its elements are named after body parts: eyes, heart, liver, knees, legs, feet, stomach, fat, and so forth. And the idiom for “drive” [a car] is identical to that for “ride” [a horse], as in: “to town—with me—it will gallop.” Is it surprising that Navajos are avid mechanics?

The Big Four material contributions of Europeans—firearms, horses, metal, and liquor—make a fascinating chapter in Navajo etymology. For guns there was no cultural precedent, so the name is a verb for “explosion.” (Other tribes reportedly said “thunder stick” or “kills at a distance.”) The horse was given an ancient name for “pet.” In the origin story, Sun had three water monsters as pets or familiars. And Changing Woman gave a pet to each “earth-surface” family. The noun stems for these are the same as for horse.

Metal is named after “stone knife,” another pan-Athabascan noun stem. The old word was first attached to “metal knife,” then (by extension) to any metal object. “Stove,” for example, is rendered by a construction meaning “metal—in it—fire.” The May 1997 cover of the magazine Wired carries a Navajo phrase which I translate as “metal flexibly extending” (i.e., telecommunication). The –ho– prefix, of course, is present (see below).

Before the advent of liquor, Navajos made a drink from fermented corn, called “grey water.” This was abandoned (after all, liquor is quicker), and the new drink was named “dark water.” But in Navajo there are two concepts of “dark”: earth darkness and that of the four lower worlds. Probably owing to its social toxicity, liquor is named after the latter.

Before we call this naming behavior quaint, think back to how 17th-century Europeans improvised an entire terminology for finance and manufacturing. Talk about strange!

7. Kinship terminology. Navajo children grow up in a matriarchy, cared for by their mother and her female relatives. As a result, the term for “aunt” is different for father’s sister.

See how the “pen of my aunt” shows us much about Navajo life and language! I’ll close by describing an entrancing Navajo language phenomenon: a prefix that profoundly changes the meaning of verb constructions in a way that Immanuel Kant might relish.

Navajo prefixes occupy a fixed position relative to one another, like planetary orbits (Sapir identified thirteen, some mutually exclusive). Consider this simple stem-and-prefix construction: “I toss a round object [say, a ball] through a narrow opening [say, a door].” The stem, recall, is one of a class that specifies the general nature of objects handled. The prefix has an equally generic meaning that might reference a doorway, corral gate, or rock cleft (from which water flows). Words specifying “ball” and “door” are not strictly necessary, because these are implied by verb-embedded clues, and by other context.

Now insert the ubiquitous prefix (-ho-) as a semantic catalyst, and the meaning is profoundly altered. The speaker is now saying, “I’m telling a story.” The semantic contribution of the prefix is to signal a “mind-body event”! With the prefix, the round-object stem denotes stories, songs, ceremonies and even contracts, perhaps because these have a beginning, middle, and end (hence their “roundness”). Another stem, that for a flexible, rope-like object, can take on—with the prefix—the meaning of “longing.”

The same prefix has two other very different meanings, depending on the context. A pan-Athabascan verb stem describes the slow linear movement of ceremonial dancers. Prefixed by –ho– , the construction now denotes the passage of time! A similar metaphor is based on a stem whose primary meaning is “horizontal extension,” say, of a rock ledge. With the prefix, we have “time extends.” Powerful imagery, so different from ours. Yet not entirely, as in “Time, like an ever-rolling stream” and “Time’s winged chariot.”

The third meaning of the prefix speaks to the general character of space. A certain white-appearing valley near Chinle, Arizona is described by a verb stem denoting “whiteness,” plus the prefix. Thus the meaning is lifted from a particular whiteness to spatial whiteness.

Is this stunning linguistic invention, or what? Then stir in this thought: acquaintance with the epistemology of Kant suggests, at least to me, a parallel between the three semantic realms opened by the –ho– switch and the three dimensions which humans, according to Kant, bring to the processing of perception, namely, mind, time, and space.

What an absurd connection to propose! How could a few thousand sub-Arctic scrabblers, lacking an Academy or even an ad hoc committee of grammarians, plan a language whose key semantic elements—the stems and prefixes of verbs—are so generic that “actionable meaning” results only from the semantic intersection of these elements, denotationally weak in themselves? Then, from this already lofty scaffolding of abstractions, what led the committee to devise a further prefix serving as a gateway to yet another level of abstraction?

Creativity seems indicated. Far from being a clumsy creole of disparate grammatic devices, Navajo is elegant to the point of beauty precisely because of its radical design decisions. Thomas Mann, in Magic Mountain, speaks of the collective and anonymous creative style of medieval times. Certainly “collective and anonymous” must also govern the evolution of language, but the creative source of its formal elegance remains elusive.

It’s worth studying the shape, idiom, and history of at least one remote language within a conceptual frame that nurtures our wonder at human inventiveness. And this “new philology” should be written to provoke a wider audience than professional linguists choose to address. The cryptic messages embedded in these perishable time capsules make too exciting a chapter in our shared human history to leave to specialists.

[David Cates was a long-ago grad student in linguistics and anthropology at University of Chicago, but keeps in touch with Navajos, though less fluently now. Other interests are chamber music and video-making.]

SIC! SIC! SIC!

Notice on Moorgate Underground station, London: Notice to passengers: this exit is an entrance. [Submitted by Tony Hall, Aylesbury, UK]

British Football Chants

Pete May, London, England

Only in Britain would Manchester United’s David Beckham have to suffer several thousand football fans chanting “Posh Spice takes it up the arse!” sung to the tune of the Pet Shop Boys' Go West. Since he married Spice Girl Victoria Adams, poor Beckham has been the butt of much obscene chanting. It started off two years ago when West Ham fans chanted “Posh Spice is a dirty slag [prostitute]!” at Beckham and he responded with aggressive gestures.

This was a mistake. Even if the chants do come from fat blokes with a hang-up about anal sex, most of them can be mollified by a humorous response; the worst thing a footballer can do is show anger, because he will then be baited even more. Beckham has suffered so much from fans envious of his millionaire status, celebrity marriage and good looks, that the Professional Footballers' Association chairman Gordon Taylor recently called for fans to lay off Beckham. Posh Spice herself has shown more of a sense of humour, and has even said in an interview that “I want to say to them ‘actually I don’t!'”

The first thing that will strike a newcomer at a British football match (it’s called soccer in the U.S. but, although the word is recognised in Britain, it is rarely used) is the number of taboo words used in chants, such as wanker (an English term for a masturbator), arse, shit, fucking and cunt. The record for swearing is probably held by the Arsenal fans’ dirty ditty (sung to the tune of the 1960s hit My Old Man) of “My old man said be a Tottenham fan, I said fuck off, bollocks you’re a cunt!”

Although many clubs had songs from pre-war times, chants really developed in the mid-1960s. It was a time when British society was much more restrained by notions of class and “the stiff upper lip”, and for many fans chants were a glorious release from dull jobs and social convention. At first they were just impromptu terrace choirs singing pop songs such as You’ll Never Walk Alone, as at Liverpool. But slowly they developed into adaptations of tunes that quickly spread across the whole country.

Weekly football matches presented a splendid opportunity for mainly working class males to revel in obscenity, merged with a juvenile delight in using such words in the company of several thousand other fans. They emphasise tribalism, but there is more to chanting than that. For most fans there has always been something pleasingly childish and very funny about 30,000 fans simultaneously chanting “The referee’s a wanker!” particularly when it’s picked up on TV recordings.

There’s also something of the adult nursery rhyme about footie chants. I first noticed while looking after my one-year-old daughter how much she enjoyed football chants adapted to childcare needs: for example nappy changing was accompanied by chants of “On with the nappy, we’re going on with the nappy” a variation on the “Sing when you’re winning, you only sing when you’re winning!” chant.

In a similar fashion to how a toddler spots an animal, there was an incident at Liverpool in the 1960s when a cat ran on the pitch. The fans would normally chant “Attack! Attack! Attack! Attack! Attack!” at their team, but when the feline appeared they instantly chanted “A cat! a cat! a cat! a cat! a cat!”. Another chant that would be recognisable in a nursery school is that of “Ee-aw! Ee-aw!” directed at any player deemed to be a “donkey”—a clumsy, untalented performer.

And, as in nursery rhymes, there’s a strong sense of rhythm, as exemplified by Manchester United’s fans staccato homage to Eric Cantona. “Oooh aah Cantona! I said oooh aah Cantona!” Some of the repetition is also reminiscent of children’s songs—a popular chant of the 1980s was sung to the tune of The Dambusters' March and directed at the successful but reviled Leeds United. It went: “Leeds, Leeds and Leeds and Leeds and Leeds, Leeds and Leeds and Leeds and Leeds, Leeds and Leeds and Leeds, we all fucking hate Leeds!” (Not too difficult to learn the words to that one.) And the chant of “Big nose, he’s got a fucking big nose!” aimed by rival fans at Southampton’s Matt Le Tissier is an example of pure playground humour.

The British football chant is also closely aligned to pop culture— although the odd chant is sung to the tune of something more traditional, such as the anti-referee tirade of “Who’s the wanker in the black?” which is sung to the tune of the hymn Bread of Heaven.

In fact, chants are a living memorial to some now-forgotten bands. Who would remember “one-hit wonders” Chicory Tip were it not for the immortalisation of their 1970s hit, Son of My Father, as a football chant? It started off as a declaration in favour of a particular player, such as Leicester City fans' “Oh Frankie Frankie Frankie, Frankie Frankie Frankie Worthington!” This was immediately modified by opposition fans to “Oh wanky wanky wanky, wanky wanky wanky Worthington!”

Nearly thirty years later the tune is still used. When Teddy Sheringham moved from Tottenham to Manchester United in pursuit of trophies but suffered a barren first season, Arsenal fans taunted him with chants of “Oh Teddy Teddy Teddy, went to Man United and you won fuck all!”

When United won the Treble (English League Championship, FA Cup and European Cup) last season this chant no longer applied, but rival fans quickly adapted it to “Oh Teddy Teddy Teddy! Went to Man United and you’re still a cunt!”

Another relatively unknown band, Middle of the Road, have also gained footballing longevity through their song Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep. Its chorus of “Where’s your mamma gone?” was often changed to “Where’s your fatboy gone?” and directed at the clubs of Paul Gascoigne, a former England midfielder with a well-chronicled weight problem.

While the initial chant can be simply prosaic, insulting or abusive, many develop to become fine examples of a genuinely adaptive wit. For example, players are often greeted by the cry of “One Denis Bergkamp, there’s only one Denis Bergkamp!(insert player’s name of choice)” sung to the tune of the Spanish song Guantanamera.

When England played in the 1986 World Cup with two defenders named Gary Stevens in the squad, this was cleverly adapted by England fans to “Two Gary Stevens! There’s only two Gary Stevens!” Even better was the version from Kilmarnock fans in Scotland. They sang “Two Andy Gorams, there’s only two Andy Gorams!” at the Rangers goalkeeper, who before the match was said to be “mentally unattuned”. When a fat player is spotted he is taunted with “One Teletubby, there’s only one Teletubby!” a reference to the podgy characters in the pre-school children’s programme.

In turn, the song became “Sing when you’re winning, you only sing when you’re winning!” directed at the opposing fans who sing when they take the lead. When sides played Grimsby, a side from a port, their fans chanted “Sing when you’re fishing, you only sing when you’re fishing!” The Grimsby fans liked this so much that they began themselves to sing “Sing when we’re fishing, we only sing when we’re fishing!” and a group of supporters even entitled their fanzine Sing When We’re Fishing. Another version was “Score in a brothel, you couldn’t score in a brothel!” used when a player misses with his shot.

A variation on the numbers theme came at the beginning of the current season when West Ham had just signed the Costa Rican striker Paulo Wanchope, pronounced “one-chop”. The opposition Spurs fans responded with the chant of “You’ve only got Wanchope!” this time to the tune of Blue Moon.

Sometimes a chant is tailored exactly to the play. One of the silliest is “Woooooooh! You’re shit! Aaargh!” This occurs when a goalkeeper takes a goal kick. A group of fans will give an extended “Whoooooah” during his extended run-up, followed by a staccato “You’re shit! aaaargh!” as he kicks the ball.

Chants reflect the social climate of England. In the 1970s and 1980s, when there was a big problem with football hooliganism, there were aggressive chants such as “You’re gonna get your fucking heads kicked in!” In the 1970s, skinhead fans indulged in “aggro”, short for aggravation. “Aggro” was enshrined in a song sung to the opening section of Gary Glitter’s Hello Hello I’m Back Again! This chant went: “Hello, hello, West Ham aggro, West Ham aggro, hello hello . . . ” and would accompany the first sign of trouble in any part of the ground. Another chant from that time is “Come and have a go if you think you’re hard enough!” which has gained retro-chic and is now the title of the letters page in the British lads' mag Loaded.

But in the 1990s, all-seater stadia, higher prices and Sky TV coverage have meant the game has become largely free of trouble, and it is now an increasingly middle-class and trendy sport. In the 1980s only real fans would admit to following football, but today celebrities and intellectuals have all been desperate to declare their love of the game. In this climate chants have centred less on violence and more on humour, encouraging your side and denigrating the opposition.

Where once there was outright hostility there now tends to be irony. These days a bad piece of play from the opposition causes taunts of “You’re not very good, you’re not very good!” to the tune of the old London song Knees Up Mother Brown.

One of the most popular chants of the past decade has been the Arsenal fans' adaptation of the chorus of The Pet Shop Boys' Go West. This started off as simply “One-nil to the Arsenal!” a song that celebrated Arsenal’s frequent victories by this very score. This was rapidly adapted by other fans to “You’re shit, and you know you are!” Numerous other versions followed, including “One-nil to the referee!” when a ref was thought to be biased and the already described Beckham/ Posh Spice insults.

When Aston Villa striker Stan Collymore was exposed in the British tabloids as having beaten up his girlfriend (the TV presenter Ulrika Jonsson) in a Paris bar, fans ridiculed him in their usual merciless fashion. At first there were chants, again to the tune of Go West, of “You’re shit and you slap your bird [girlfriend]!” Even worse, when Collymore checked into a clinic and stated he was suffering from depression, he was mocked with chants of “You’re mad and you know you are!”

When the comedians Baddiel and Skinner recorded the excellent pro-England song Three Lions for the 1996 European Championships, its chorus of “It’s coming home, it’s coming home, it’s coming, football’s coming home”, became another fans' classic. Although it was soon made cruder and used in chants such as “You’re full of shit, you’re full of shit, you’re full of, Tottenham’s full of shit!” When star striker Alan Shearer left Blackburn for his native Newcastle, the club’s fans were taunted with “He’s fucked off home, he’s fucked off home, he’s fucked off, Shearer’s fucked off home!” With similar crudity, Chelsea’s adaptation of The Red Flag to “We’ll keep the blue flag flying here”, was altered by the club’s rivals to “Stick your blue flag up your arse!”

Black humour is a particular English strong point. After all, very few clubs actually stand a chance of winning anything, as there are only three major trophies, so the stoic acceptance of adversity has long been a source for songs. A goal drought can cause chants of “Will we ever score again?” (to the tune of Bread of Heaven). Even Vera Lynn’s We’ll Meet Again was adapted by long-suffering West Ham fans to “We’ll score again, don’t know where, don’t know when, but I know we’ll score again one sunny day!”

Fans are becoming ever more surreal. When Manchester City were struggling in division one, the club’s fans started singing, to the tune of Knees Up Mother Brown, “We’re not really here! We’re not really here! We’re not really, we’re not really, we’re not really here!”—surely a classic of its type.

In short, the British football chant is adaptable to just about any event that might happen on or off the pitch. Chants are subject to a kind of natural selection, which is why the best have survived for decades. They are frequently crude, childish and decidedly non-PC—but they’re also the reason many of us find live football such an enticing experience. And if you’re still mystified by this Brit disease, then there is a football chant that can be utilised. It expresses intellectual scepticism and goes: “You what, you what, you what, you what, you what?”

[Pete May is a freelance journalist based in London. He is the author of Sunday Muddy Sunday (Virgin), a study of Sunday league football teams and co-author of The Lad Done Bad (Penguin), a humorous look at sex, sleaze and scandal in English football.]

SIC! SIC! SIC!

Instructions on pot of face cream: Rub in the cream until it visibly disappears. [Submitted by Tony Hall, Aylesbury, UK]

INTER ALIA

The First Annual Willard R. Espy Light Verse Competition

To commemorate a modern master of Light Verse, LIGHT: The Quarterly of Light Verse is establishing, beginning in the year 2000, the first Willard R. Espy Light Verse Competition. This shall be in any of the traditional light verse forms (epigram, ballade, villanelle, limerick, clerihew, river rhyme, double dactyl, etc.) but may include any verse that contains rhyme and meter. The length limit shall be forty lines, and the deadline July 1st of each year, beginning in 2000. The winners shall be published in the Spring issue of the following year. There may be only one entry per contestant. First Prize will be $150, Second Prize $100, and Third Prize $50. Two Honorable Mentions will receive Willard Espy’s The Best of an Almanac of Words at Play (Merriam-Webster). All entries must include a self-addressed, stamped envelope. There will be no reading fee. No further guidelines are available; do not phone, e-mail, or fax. Send entries to LIGHT QUARTERLY, PO Box 7500, Chicago, IL 60680.

Excerpts from the Baylor College Linguistics Scavenger Hunt

M. Lynne Murphy, Waco, Texas

-

the word for “cheese” in Estonian

-

the longest word in English that uses no letter more than once

-

the name, nationality, and profession of the inventor of the Volapük language

-

a nine-letter English word that has only one syllable

-

the sound that a dog makes in Swedish

-

a language that has only three vowel sounds

-

the regional word for “drinking fountain” that’s used in Wisconsin

-

four different sounds that the letter “s” can symbolize in English spelling (examples)

-

the language that Jesus spoke

-

the American equivalent of the British word “ex-directory”

-

five words that are legal plays in Scrabble and that have only two letters, one of which is “x”

-

a language that doesn’t have the sound /t/

-

a language whose standard word order is Verb-Subject-Object

-

the motto of the Klingon Language Institute

-

a language-related holiday and the country that celebrates it

-

a word that’s included in the Oxford English Dictionary that means “a person whose hair has never been cut”

-

identity of the person who said “England and America are two countries divided by a common language”

-

five-letter English word that’s pronounced the same when you delete four of its letters

-

name of the straight line that is used over vowels to signal that they are so-called “long vowels” (e.g., in dictionary pronunciation guides)

-

what “apples” means in Cockney rhyming slang

[Answers to be found on page 14.]

From Josephus’s Jewish War to the American Civil War: Charles Francis Adams, Jr.’s “Dead Sea Apple”

Michele Valerie Ronnick, Wayne State University

The only example of the phrase “dead sea apple(s)” used during the past 150 years is dated to 1869 by the Oxford English Dictionary. The entry states:

Hence forming part of the name of a large number of fruits; as apple Punic, obs. name of the pomegranate; apple of Sodom, or dead Sea Fruit, described by Josephus of fair appearance externally, but dissolving, when grasped into smoke and ashes; a traveller’s tale supposed by some to refer to the fruit of Solanum Sodomeum (allied to the tomato) by others to the Calotropis procera; fig. Any hollow disappointing specious thing.”

The OED editors then quote from The English Mechanic and World of Science, published from 1865 to 1923 in London by E. J. Kibblewhite: “1869 Eng. Mech. 24 Dec. 354/1 Mecca galls, Dead Sea Apples, Sodom Apples, or mad apples . . . are occasionally imported from Bussarah.”

The connection with Josephus is based upon a passage about the city of Sodom found in his Jewish War. Describing the fruits grown in the now blasted and cursed land, he states that “one can see cinders reproduced in the fruits, which from their outward appearance seem edible, but after being plucked by hand disintegrate into smoke and ashes.”4

A striking, but heretofore unnoticed, occurrence of the phrase is found in Charles Francis Adams, Jr.’s assessment of his service with the Union forces during the Civil War. Upon his enlistment in 1861 his mood was one of jubilation. Charles Jr. declared in a letter to his father Charles Sr. in 1862: “I would not have missed it [his first experience under fire] for anything . . . the sensation was glorious, . . . Without affectation it was one of the most enjoyable days I ever passed.”5 By 1864, however, his views had changed. In a letter to Henry Adams dated July 22, he wrote: “My present ambition is to see the war over . . . I am tired of the Carnival of Death.”6

In 1916, the year his Autobiography was published, he closed the chapter entitled, “War and Army Life,” with this summation: “As it was in June, I think, I was quietly mustered out of the service, and became once more a civilian. A great experience was over, and its close was for me a Dead Sea apple. But I intended it well!”7

How the term came into Adams' vocabulary is not clear. In his undergraduate years at Harvard he had in his own estimation “rather a fancy for Greek”. . . and . . . “came within an ace of being a fair Greek scholar.”8 He might well have read Josephus' original text in Greek, however the noun Josephus used meant fruit in general, not apple specifically. But regardless of Adams' source, his words and their reference to the Old Testament city of Sodom provide us with a vivid summation of his feelings about the Civil War—one that would be instantly understood by his fellow Americans, north and south alike. For that was an era whose aesthetic was deeply influenced by the Bible. His is also the first example of the phrase in American letters.

[Michele Ronnick is an associate professor in the Department of Classics, Greek, and Latin.]

Linguistics Scavenger Hunt Answers

-

juust

-

uncopyrightable

-

Johann Martin Schleyer, German priest

-

strengths or screeched

-

vov vov

-

There are a few of these: Gudanji, Aranda, Greenlandic, Amuesha, etc.

-

bubbler

-

Voiceless alveolar fricative (in sit), voiced alveolar fricative (in busy), voiceless palatal fricative (in sure), voiced palatal fricative (in pleasure)

-

Aramaic

-

unlisted (phone number)

-

ax, ex, xi, ox, xu

-

Hawaiian

-

There are a number of these: Welsh, Tongan, Squamish, Tagalog, Maori, etc.

-

“Language opens worlds.” See www.kli.org for the Klingon version.

-

Hangul day—Korea (celebrates the Hangul writing system)

-

acersecomic

-

George Bernard Shaw (other people who have said it were quoting Shaw!)

-

queue

-

macron

-

from “apples & pears”—means “stairs”

CORRIGENDA

In the Autumn 1999 issue there were (at least) two errors. First, we left contributor Howard Richler’s name off his review of the new Microsoft Encarta World English Dictionary. Mr. Richler writes from Montreal, Canada. Also, we misidentified the makers of Crayola brand crayons. They are, and have always been, Binney and Smith, rather than “Binnie and Smith.” Our apologies for these oversights and errors.

OBITER DICTA: To What End Gender Endings?

Susan Elkin , Sittingbourne, Kent

Was John Knox merely respecting a 16th-century lexicographical nicety when he referred to Mary Queen of Scots as ‘a Cruell persecutrix of goddis people’? Or was he having a dig at her for being not only a monarch he resented for her Catholicism and unsympathetic ways, but also for having the effrontery to be female?

There used, in the middle ages, to be a whole raft of these neat feminine nouns with a -trix, or sometimes -trice, ending. They came from Latin agent nouns ending in -or. Thus, in the unlikely event of an adjudicator being a woman, she was carefully called an adjudicatrix. And commanders, or imperators were chaps, of course. But if, by any faint chance, one wasn’t, she had to be an imperatrix.

Chaucer wasn’t having any nonsense about fortune being anything but female either. ‘But, O Fortune, executrices of weirdes’, he wrote in Troilus and Criseyde (1374). Then there was bellatrix—it was interchangeable with bellatrice—for a war-waging woman on the rampage, like Boudica.

An inventrix was a female discoverer like . . . well, can you think of a medieval one? Perhaps that’s why the word was never in common use. And a venatrix was a female hunter, like Diana, Roman goddess of the moon. Sadly, no one seems to have used the rather splendid ultrix, an avenging woman (although I bet there have been plenty of them down the years) since Caxton in the fifteenth century.

Later words such as administrix, consolatrix, mediatrix and testatrix evolved. And by analogy there were coinages such as inheratrix, narratrix and perpatrix.

Some were quite common even in the nineteenth century. ‘In his victrix he,'—Charlotte Bronte’s Dr John in Villette (1853)—‘required all that was here visible.’ It was meant to be a marriage, not a war, but Charlotte Bronte manages to take a thumping sideswipe at this relationship in that one word, victrix.

Anthony Trollope did something similar in Barchester Towers (1857) by naming a chapter Mrs Proudie Victrix. In the power struggle between the bishop’s termagant wife and his slimy chaplain, Obadiah Slope, at this stage in the novel Mrs Proudie is winning—to the fury of everyone in male-dominated diocesan politics.

When Amy Johnson et al took to the air how could they possibly be described as aviators as if they were men? The word aviatrix had only a short life. So did the word oratrix—presumably because by the time women were no longer expected to be seen and not heard, like their children, orators like Margaret Thatcher and Golda Meyer had to compete on equal terms with men. It’s the same with Hillary Clinton today.

Even today I am carefully described in the legalese of my sister’s will as her executrix. Yes, the lawyer seems to be saying, let her execute the will but only because we couldn’t persuade the client to appoint a man.

And dominatrix has acquired a whole new meaning in the sex-obsessed present. In the 17th century it just meant a bossy woman. The sado-masochistic overtones are new.

The commoner feminine ending for -or and some other words is, of course, -ess. Vicaress and rectoress, which just meant wife of a vicar or rector in the 18th century, have disappeared. And saviouress, a use of which was recorded in 1553, along with farmeress, which had a brief innings in 1672, seem never to have progressed beyond the fanciful stage.

But there are plenty of very ordinary everyday -ess words. Lioness, duchess and hostess, for example. Yet even some of these are on the slippery slope of political correctness.

The mainstream press will still refer to, say, Dame Judi Dench, Meryl Streep or Helen Mirren as “a fine actress,” but you won’t catch a glimpse of the word in The Stage Newspaper, the weekly trade journal of the British show business industry. Here, in both advertisements and editorial copy, everyone is referred to as an actor. All actors are equal—without the Orwellian corollary.

And have you noticed the job snobbery which hangs murkily around the word manageress? If you wear a pinny and run a teashop or a twee hairdressers, it seems to be OK to be a manageress. But if you wear a dark suit and are in charge of an investment fund in a merchant bank, then you’ll be a manager, irrespective of sex.

The John Knoxes are still among us, waxing critical. There was something medievally spiteful about the way that a few detractors of British women priests in the early 1990s tried to dub them “priestesses”—as if they weren’t Christians. It was a classic example of using a gender suffix for negative reasons. I’m glad it didn’t catch on.

[From her base in southern England, Susan Elkin writes for publications as various as The Times, Daily Mail, The Daily Telegraph, The Stage, Music Teacher, In Britain, and Traditional Woodworking. Her books include a biography, two English literature study guides, and eight education reports. Susan has been in love with words and books for as long as she can remember.]

DACTYLOLOGIA

The televisions and atomic bombs above are from the Church of the Subgenius BOBCO8 font. They are copyright the Church and shareware ($20). More information is at www.subgenius.com/SUBFONTS /subfont.html.

From Ragusa to Lombard Street

Martin Bennett, Saudi Arabia

While the Common European currency has its detractors, the international sharing of words has long been a fact of life. Here, at least, is a type of coinage beyond any government’s control. Even the Bank of England, that symbol of national sovereignty, can trace part of its name to the lowly bench, or banco, from which the first Italian money-lenders conducted business. It also provides a good starting point for this brief guide to English’s etymological debt to Italian.

To continue the financial theme, take the word cash. Its origin, however distant, is from cassa, the Italian chest where the cash was kept. Perhaps this was in florins—from Florentine fiorentini. Or as likely in ducats, a silver coin first minted by Roger II of Sicily, and later by Giovanni Dandolo, Doge of Venice, the latter coin bearing the motto ‘Sit tibi, Christi, datus quem tu regis iste ductatus’, the last word of which perhaps furthered the currency of its name. A lesser Venetian coin resurfacing in English is the gazeta, one of which could once purchase a gazetta della novia or ‘a half-pence worth of news’.

As for quantity, we have the introduction into English of the word million from milione, reminding us how Tuscan or Lombard bankers once financed the wars of English kings. The fact that credit (credito) was not always paid back is shown by the adoption of bankrupt from banco rotto (literally ‘broken bench’, an early banker’s sign of insolvency). (More happily linked with banco is banquet, this deriving from banchetto—a diminutive of banco, originally a trellised table on which the banquet was spread.)

Not that the traffic (yes, from the Italian traffico) between England and Italy was purely financial. Venice and Genoa both had mighty fleets whose frigates (fregate), caravels (caravele), barks (barche) and brigantines (briganti,. or pirate ships) all docked in English ports. Then from Ragusa, a port on the Dalmatian coast, comes the word argosy, although the English word has an older form, as in ‘Ragusyes, hulks and caravels and other rich-laden ships.’ (Dr John Dee, ‘The Petty Royal Navy’, 1577.)

And so to cargoes and contraband (a telescoping of contra bando, literally ‘against edict’). As often happens, the names of imported goods get wrapped up in the port of origin. Examples are Marsala, the wine from there; bergamot, the oil and essence from Bergamo; baloney, a type of sausage from Bologna; travertine, a limestone from Tivoli on the River Tevere, or Tiber. Less obviously bronze (bronzo) has been traced to Brindisi, where bronze mirrors were made. Millinery was first associated with Milan, albeit hats were one item among many: ‘The dealers in various articles were called milliners from their importing Milan goods for sale, such as brooches, spurs and glasses’ (Shorter Oxford Dictionary). Another item milliners might once have dealt with was porcelain. Originally this was the name for the Venus shell, or cowry. Its shape and sheen, by a rather obscene twist of the imagination, reminded medieval traders in the East of the vulva of a porcellana, or small sow. So goes one possible etymology. Webster, more delicately, contents himself with, ‘The shell has the shape of a pig’s back and a surface like porcelain.’

Relating to the early arms trade, cannon is from canone, an augmentative form from canna, a cane or tube. Pistols derive from Pistoia, a town once also called Pistolia, once famous for its daggers, or pistolese, a word later transferred to the firearm. Then we have the musket. Rather tortuously the Elizabethan translator John Florio says this derives from moschetta, this name not of a small fly but a hawk, a footnote adding that the names of firearms were often derived ‘from dragons, serpents or birds of prey in allusion to their velocity.’ For dealers in fakes we have another Italian loan-word, charlatan, from ciarlare, ‘to chatter,’ an ingredient of his sales pitch.

So much for words directly from Italian, albeit most of their endings have been eroded by time in contrast to more recent borrowings (papparazzi; tortellini). For other words, Italian is less a port of origin than an entrepot, or halfway house. So, however far-fetched, tulip winds back via tulipinno to the Turkish tulpend and then the Persian dulband until only the shape remains, not of a flower but a turban. Bergamot—not the essence mentioned above but the type of pear derives via Italian’s bergamotta from Turkish beg armud, literally ‘prince of pears.’ (Helping explain the etymology, history notes how by 1507 there were agents of 60 or more Florentine firms in Constantinople.) Scimitar (Italian scimitare) has its origin in the Persian Simsir. Meanwhile there is a whole cargo of English words which can, following the old trade routes, be traced back through Italian to Arabic. Artichoke—articiocco—al-kharshuuf. Arsenal (Highbury)—l’Arsenale (Venice)—dar as-Sanaa (Arabic, ‘house of work’). But the items on the list run to dozens.

Yet the traffic of words mentioned in the title has been far from one way. English, in turn, has provided Italian with pure anglismi such as fifty-fifty, egghead, sponsor, babysitter and bypass. Other anglismi have a more local character. So puzzle is rephoneticised into ootzlay; pocket radio is inverted to radio pocket; handicapped becomes handicappato; a top model is simply una top. Snob produces a name for not just a string of Italian boutiques, but another verb, snobbare with a corresponding gamut of Italian inflections. Likewise from click we get cliccare to set alongside the uninflected software and hardware.

Outlandish coinages? Perhaps. Except the host language, whether in Rome or London, seems to have its own mechanism for incorporating them until the same coinages become standard lexical currency.

[Martin Bennett read English at St Catherine’s College, Cambridge, and then taught English and French in West Africa. He now teaches English and Italian in Saudi Arabia. An article on Arabic proverbs—“The Lamps of Speech”—appeared in a previous edition of VERBATIM.]

HORRIBILE DICTU

Mat Coward, Somerset, England

I suspect that issues has been an irritating word for some time. Certainly, I remember it being overused in left-wing and trade union circles twenty-odd years ago, when it meant something like “matters upon which we are or should be campaigning”. There were also issues around, as in “we are working on issues around immigration,” where around meant “to do with”.

A narrower usage (of US origin, I presume) has recently become common in the UK, under which issues (invariably plural) are no longer merely and neutrally topics of interest, but problems, disagreements or dislikes. The phrase “You have raised an interesting issue” will soon, I imagine, be meaningless to anyone under the age of thirty.

An American contributor to an e-mail list discussed the difficulties of looking after a disabled baby, “which has meant all kinds of doctors’ appointments and special feeding issues”. A recruitment advertisement in a British newspaper, for the post of “Head of Equalities” at a county council, was accompanied by a picture of a dartboard. The caption read: “Imagine the board is equal opportunities issues. The darts are people’s attempts to manage them and the holes are the ones in their thinking”.

In another UK newspaper, a writer argued that institutionalised racism was not unique to the USA: “There can be no doubt that Britain has its own issues regarding race”.

When work on an £18 million leisure complex development in Hampshire was halted because the site was found to be home to an endangered species of dragonfly, a spokesman for the developers told reporters “We are resigned to dropping the project . . . we respect green issues.” That application is especially baffling; how does one “respect” a problem, or indeed a topic?

Perhaps issues is not properly a Horribile, no matter how ugly it sounds to many of us, but rather a word undergoing a transitional period of vagueness; having been stripped of its familiar meaning, it has not yet been assigned a new one, and is therefore available to fill in on a temporary basis as and when required.

Other words on the move include advice, which seems to be taking on a more sinister role. When South Wales police charged an officer with neglect of duty and discreditable conduct, newspapers reported that “another officer is to be admonished and three others will receive ‘advice’”. The inverted commas, and the context, suggest that this advice forms part of a disciplinary, and not an educational, process.

Ethnic (now commonly a euphemism for “non-white”) and literally (increasingly used to mean either “very” or “metaphorically”) will require a column to themselves. Meanwhile, have you noticed what is happening to officially?

In 1999, the England cricket team fell, for the first time, to the lowest position in an unofficial league table. Every newspaper report I read of this major national tragedy declared in its headline or opening paragraph that England was “officially the worst team in the world”—although many of them then went on to explain the unofficial nature of the unsought title!

Officially was therefore being used to mean “definitely” or “undeniably”. I lack the learning to name this phenomenon, but it seems to me that words which are useful precisely because their purport is narrow or broad are rendered “lite” when their precincts are stretched or straitened.

And, to quote a politician I recently heard interviewed on the BBC, “Inevitably, one could have issues with that”.

(Readers are invited to suggest “issues” for this column, or to supply further examples of those already discussed. Please contact me via VERBATIM’s UK or US offices. My thanks to those who have already been in touch— be assured that all your contributions are read, enjoyed, and carefully filed for future deployment).

INTER ALIA

We all have had the experience of finding an intriguing word in the dictionary when we were supposed to be looking up something else, but Dr. Mardy Grothe has turned his experience into a charming little book of quotations, each and every one of which is an example of chiasmus.

What’s chiasmus, you ask? Well, besides being the word that distracted Dr. Grothe from his original target, it’s the reversal in the order of words in two otherwise parallel phrases. The title of the book is itself chiastic: Never Let a Fool Kiss You or a Kiss Fool You. (ISBN 0-670-87827-8)

If, after reading this book (actually, I recommend dipping into it at random; if you read the whole thing straight through you’d probably speak in chiasmus the rest of the day!) you want more, check out www.chiasmus.com, where there will soon be a chiasmus email mailing list.

My favorite quote in the book? “It is well to read everything of something and something of everything” (Henry Brougham). Make this book one of either somethings. -Erin McKean

EPISTOLA {Matthew Perret}

I was most interested to read the article “Identity and Language in the SM Scene,” by M. A. Buchanan in the Summer issue (XXIV/3).

But I think the comment that there is no Spanish equivalent for the English terms boyfriend and girlfriend is inaccurate. I believe the terms novio and novia convey the modern American meaning the author refers to—at least these days. My Spanish-speaking gay friends use the term to refer to their partners, as do straight couples who have no intention of marrying.

The time that people seem to move away from the terms, and use such “modern” terminology as compañero sentimental or pareja (loosely, ‘partner’) instead, is when they reach an age at which the term seems odd. (And after 20 years of cohabitation, would English-speaking couples still speak of themselves as “boyfriend” and “girlfriend”?) In both languages, the terms suggest relative youth, and experimentation. Each culture then has its own tradition of formality, or lack of it, in pre-nuptial relationships.

Incidentally, Gerald Brenan, in his book South from Granada, describing southern Spain in the 1920s (in many ways a deeply conservative Catholic society), says that it was considered quite normal for a girl to have many “novios”.

Limits on acceptable behaviour may be encoded into our language, yes: but people still continue to use words to mean what they want them to mean. My last “girlfriend”, who was Spanish, called me her “novio”; but she didn’t believe in marriage.

[Matthew Perret, Brussels, Belgium]

EPISTOLA {Matthew Perret}

While I do not know the meaning of the Thai word (from “On the Use of Niggardly”, 24/4) the anecdote reminded me of a story from a friend who served in the Army during the second world war. After weeks in the field, he was assigned for a few days of respite to live with a family in the Flemish-speaking part of Belgium. Almost his first request was “Wash my clothes please.” This was greeted with stunned silence since the Flemish word for “testicles” was pronounced “clothes.”

[Quincy Abbot, West Hartford, CT]

Have Your Salt and Eat It, Too

Steve Kleinedler, American Heritage Dictionaries

It’s dinnertime, and you’re about to enjoy a tasty meal, but you find the food in need of seasoning. You ask the resident sarcastic adolescent at the opposite end of the table, “Can you pass the salt?” and you get the terse reply, “Yes,” but you don’t get any salt.

Protestation only elicits the response: “But you didn’t ask if I would pass the salt, you asked if I could pass the salt, and yes, I’m physically able to do so.” Depending on the way your household functions, you may end up with screaming parents, a punished child, passive-aggressive silence, or possibly some salted food. You know that you know what the kid meant, but in your head there’s a small voice thinking, well, I suppose technically that’s what can means.

Actually, you should trust your initial instinct. What the surly teenager has done is perversely ignored a maxim of conversational implicature, and in doing so, disregarded an indirect speech act.

Within the linguistic subfield of pragmatics, implicature, presupposition, entailment and indirect speech acts have long been a focus of inquiry, with countless philosophers picking apart sentences such as “The King of France is bald.” Among the topics most fun to explore is conversational implicature.

For an appropriate starting point, we turn to H. Paul Grice, a British-born philosopher who taught at Berkeley for much of his career. In 1967, he delivered his William James Lectures at Harvard University. One significant lecture first appeared in print as “Logic and Conversation” in 1975 in the third volume of Syntax & Semantics. Many subsequent works concerning conversational implicature and discourse theory draw from it heavily. As an added bonus, it’s fairly comprehensible to the layperson.

Grice observes that conversations aren’t usually made up of disjointed comments. Rather, speakers generally adhere to what he calls the Cooperative Principle (CP): “Make your conversational contribution such as is required, at the stage at which it occurs, by the accepted purpose or direction of the talk exchange in which you are engaged” (p. 45).

It may sound like he’s stating the obvious, but his analysis of the CP yields four conversational maxims, by which we can analyze how conversations and implications function the way that they do. These maxims are (p. 47):

The Maxim of Quantity

-

Make your contribution as informative as is required (for the current purposes of the exchange).

-

Do not make your contribution more informative than is required.

The Maxim of Quality—Try to make your contribution one that is true:

-

Do not say what you believe to be false.

-

Do not say that for which you lack adequate evidence.

The Maxim of Relation—Be relevant.

The Maxim of Manner—Be perspicuous.

-

Avoid obscurity of expression.

-

Avoid ambiguity.

-

Be brief (avoid unnecessary prolixity).

-

Be orderly.

Grice then lists four ways that one can fail to fulfill a maxim (p. 49):

-

He may quietly and unostentatiously violate a maxim; if so, in some cases he will be liable to mislead.

-

He may OPT OUT from the operation of both the maxim and of the CP; he may say, indicate, or allow it to become plain that he is unwilling to cooperate in the way the maxim requires. He may say, for example, “I cannot say more; my lips are sealed.”

-

He may be faced with a CLASH: he may be unable, for example, to fulfill the first maxim of Quantity . . . without violating the second maxim of Quality.

-

He may FLOUT a maxim; that is, he may blatantly fail to fulfill it. On the assumption that the speaker is able to fulfill the maxim and to do so without violating another maxim (because of a clash), he is not opting out, and is not, in view of the blatancy of his performance, trying to mislead, the hearer is faced with a minor problem: how can his saying what he did say be reconciled with the supposition that he is observing the overall CP? This situation is one that characteristically gives rise to a conversational implicature; and when a conversational implicature is generated in this way, I shall say that a maxim is being exploited.

The fun comes in analyzing discourse sequences to determine how implicatures are made by flouting or exploiting these maxims. Grice discusses three kinds of conversational implicatures. (The examples below are taken from his examples.)

The first group consists of “examples in which no maxim is violated” (p. 51).

Scenario: A is standing by a disabled car. B approaches:

A: I’m out of gas.

B: There’s a station around the corner.

Here, B implicates that B thinks that the gas station is probably open, otherwise B would be flouting the maxim of Relation. If both participants are adhering to the CP, A has no reason to believe that B would be flouting the maxim, and so understands that B intends A to think that at that gas station A can get gas and no longer be out of gas.

The second group consists of “example[s] in which a maxim is violated, but its violation is to be explained by the supposition of a clash with another maxim” (p. 51).

Scenario: A is going on a vacation in France. A and B both know that A wants to visit C if it’s not out of A’s way.

A: Where does C live?

B: Somewhere in the south of France.

Here, B’s answer is not as informative as A would need to make a decision as to whether C can be visited, and thus B’s response can be seen as a violation of the first maxim of Quantity. But, A would not expect B to opt out. So, A then infers that for B to say anything more informative than “Somewhere in the south of France” would violate the maxim of Quality. Thus, A infers that B doesn’t know the town that C lives in (pp. 51–52).

The third group is large, consisting of “examples that involve exploitation, that is a procedure by which a maxim is flouted for the purpose of getting in a conversational implicature by means of something of the nature of a figure of speech” (p. 52).

Many figures of speech can be explained and analyzed by this approach. Grice shows that violations of the first maxim of Quality are responsible for irony (“X is a fine friend,” when it’s obvious that X is not); metaphor (“You are the cream in my coffee”); meiosis (“He was a little intoxicated,” used of one who has trashed a room); and hyperbole (“Every nice girl loves a sailor”) (p. 53).

Violations of the first maxim of Quantity include tautology (“War is war”), but are also evident in less extreme situations such as Grice’s classic “letter of recommendation” scenario: “A is writing a testimonial about a pupil who is a candidate for a philosophy job . . . : ‘Dear Sir, Mr. X’s command of English is excellent, and his attendance at tutorials has been regular. Yours, etc.’ (Gloss: A cannot be opting out, since if he wished to be uncooperative, why write at all? He cannot be unable, through ignorance, to say more, since the man is his pupil; moreover he knows that more information than this is wanted. He must, therefore, be wishing to impart information that he is reluctant to write down. This supposition is tenable only on the assumption that he thinks Mr. X is no good at philosophy. This, then, is what he is implicating” (p. 52).

Notice that such implications can be culture-bound. I have heard that such succinct recommendations are the norm in Germany. (And if I have been informed incorrectly, it’s certainly within the realm of possibility that there is some culture where this is the norm; the point being, implicatures that one draws may be particular to a culture or subculture.)

Grice offers the following as an example of a Relation violation: “At a genteel tea party, A says Mrs. X is an old bag. There is a moment of appalled silence, and then B says, ‘The weather has been quite delightful this summer, hasn’t it? B has blatantly refused to make what he says relevant to A’s preceding remark. He thereby implicates that A’s remark should not be discussed and, perhaps more specifically, that A has committed a social gaffe” (p. 54).

Among violations of Manner are ambiguity, obscurity, and failure to be succinct. Grice invites us to compare “Miss X sang ‘Home Sweet Home’” with “Miss X produced a series of sounds that corresponded closely with the score of ‘Home Sweet Home’” (p. 55). A reviewer writing the second sentence would eschew the simple sentence to imply that her “performance suffered from some hideous defect.”

Laurence Horn, a linguist at Yale, has carried on Grice’s work. He has condensed the four maxims, focusing on one that is speaker-based and one that is hearer-based. (Others, such as Dan Wilson and Dierdre Sperber, have condensed them into one, Relation.) In a 1984 article, Horn demonstrates that these two opposing forces and their interactions are responsible for generating Gricean maxims and the inferences derived from them. Horn’s two principles are (p. 13):

The Q principle (hearer-based)

-

Make your contribution sufficient. (Cf. Grice’s first maxim of Quantity.)

-

Say as much as you can (given the R principle)

The R principle (speaker-based):

-

Make your contribution necessary. (Cf. Grice’s maxims of Relation, Manner, and the second maxim of quantity.)

-

Say no more than you must (given the Q principle).

Q-principle implicatures are very common. Examples are those that arise from scalar predictions: “Some X are p” implies “Not all X are p.” That is, “Some dogs are brown” implies “Not all dogs are brown.” If speaker knew that all dogs were brown, and if such information were relevant to the hearer, the speaker would be obliged to obey the Q principle and say so. The hearer’s assumption that the speaker is obeying Q (and thus adhering to the CP) allows the hearer to infer that the speaker does not know the stronger predication, “All dogs are brown.” to be a fact (p. 13).

Other Q examples are those that entail a lower bound (‘at least’), and implicate an upper bound (‘at most’). Conjoining these brings about conveys ‘exactly’ (p. 13). Horn offers the example “He ate 3 carrots.” This sentence entails “He ate at least 3 carrots” and implicates “He ate at most 3 carrots,” the conjunction of which gives “He ate exactly three carrots.” Intentionally violating the Q principle results in the act of the speaker intentionally misleading the hearer. That is, to say “He ate 3 carrots,” when he in fact ate 4 or 5 carrots, is not untruthful; it’s misleading (p. 14).

The R principle mirrors the Q principle. Whereas (p. 14), “a speaker who says ‘p’ may license the Q inference that he meant ‘at most p,’ a speaker who says ‘p’ may license the R inference that he meant ‘more than p.'” The most obvious examples are indirect speech acts. (This brings us back to the salt.)

Horn states: “If I ask you whether you can pass me the salt, in a context where your abilities to do so are not in doubt, I license you to infer that I am doing something more than asking you whether you can pass the salt—I am in fact asking you to do it.” If the speaker knows that the hearer is able to pass the salt, then the question of whether the hearer is physically capable of doing so is pointless. By the Relation maxim, the hearer infers that the speaker means something more than the speaker says. Intentional violations of the R principle (that is, violations of the maxim of Relation) are “merely unhelpful or perverse” (p. 14).

So, when the salt scenario looms large in your dining room, you can respond by saying “Until you can adhere to the Cooperative Principle, you are excused to your room,” and hand the violator this essay.

Grice, H. P. 1975. “Logic and Conversation,” in Syntax & Semantics, vol. 3: Speech Acts. P. Cole & J. Morgan, eds. New York: Academic Press.

Horn, L. 1984. “Toward a New Taxonomy for Pragmatic Inference: Q-Based and R-Based Implicature, in Meaning, Form and Use in Context: Linguistic Applications” (GURT), D. Schiffrin, ed. Washington: Georgetown University Press.

Sperber, D., & Wilson, D. 1986. Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

[A lexicographer, Steve Kleinedler is an editor on the staff of the American Heritage Dictionary Houghton Mifflin Co.). A University of Chicago graduate student as well, Steve needs to write his PhD dissertation. He holds a BA in linguistics from Northwestern University.]

As the Word Turns

Barry Baldwin, Calgary, Canada

Unless any scientific compound usurps it in the forthcoming new edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, floccinaucinhilipilification, as John Simon guessed in his Paradigms Lost (1981), is the longest word there. Weighing in with 29 letters, it beats by one its sesquipedalian opponent antidisestablishmentarianism.

This majestic monster found a place in Russell Rooke’s Grandiloquent Dictionary (1972), being there defined as “the action or process of estimating a thing as worthless.” Our word is compounded from four Latin expressions for such low evaluation: “non flocci facio”—I don’t give a flock for; “non nauci facio”—I don’t give three flocks for; “non nihili facio”—I don’t care nothing for; or “non pili facio”—I don’t give a hair for.

It looks like a Samuel Johnson kind of word. Celebrated for his long Latinate terms, the Great Cham defended their use in an essay in the Idler: “Few faults of style, whether real or imaginary, excite the malignity of a more numerous class of readers, than the use of hard words. But words are only hard to those who do not understand them, and the critick ought always to enquire, whether he is incommoded by the fault of the writer, or by his own.” Boswell duly defended his hero: “Mr Johnson has gigantick thoughts, and therefore he must be allowed gigantick words.”

In fact, it was William Shenstone (1714–1763) who imported our word into English, in one of his published letters, in 1741: “I loved him for nothing so much as his floccinaucinhilipilification of money.” Shenstone was best known as a poet, though no contemporary thought highly of him (“that water-gruel bard,” gibed Horace Walpole). He had no particular reputation for sesquipedalianism. His use may have been disingenuous: the poet Gray’s reaction to his Letters was “Poor man! He was always wishing for money.”

After Shenstone, the word languished a good sixty years before the poet and critic Robert Southey took it up in an 1816 essay in the Quarterly Review. Then Sir Walter Scott tried it out in a journal entry on 18 March 1829, thus: “They must be taken with an air of contempt, a floccipaucinihilipilification of all that can gratify the outward man.” This same spelling occurs elsewhere in Scott: mistake or deliberate alteration?

And that is the complete history of the word, according to the OED. Has any reader seen it in modern literature? I’ve noticed the spin-off adjective floccinaucinihilipilificatory in occasional pieces of fugitive journalism. I used to recommend the noun to my students as a good one for debates and pub conversation. Overall, it evidently never caught on. Just TOO big, perhaps?

Well, if that’s the problem, there are less jaw-breaking allotropes. In his English Dictionarie, or An Interpreter Of Hard Words (1623), Henry Coceram introduced and defined the verb floccifie (‘to set nought by’), but this one seems to have died quickly after Blount’s 1656 rehash of Coceram in his Glossography. The chronicler Edward Hall (1499–1549) had already tried out floccipend (“Every honest creature would abhorre and floccipend”) in 1548, but this one had to wait for Walter Thomson’s 1882 essay on Bacon and Shakespeare (“A profession prone to floccipend old locks of thought from wooly-headed thinkers”—a groanable triple pun) for its next outing, and it still awaits its third.

Southey himself, in critical esays of 1826 and 1829, came up with “a floccinaucical signification” and “floccinaucities to which so much importance is attached”; neither found a taker. So, if the floccular processes of your cerebellum have been flocculated by this flocculent flourish, fear not to write floccosely—English and Latin are on your side, and it beats the hell out of the Nineties Newspeak of academics and computers.

[Barry Baldwin grew up in England during and after World War II. Now in Canada, he has published 12 books and some 600 articles on Greek/Roman/Byzantine/18th-century history & literature. His chief passions are cricket, English soccer, and eating.]

A Visit from Aunt Rose: Euphemisms (and Pejoratives) for Menstruation

Jessy Randall, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Now it can be told. There are over one hundred codes for menstruation, from the gentle euphemism (that time of the month) to the vulgar (riding the cotton pony) to the downright peculiar (the woodchuck has arrived). Some of the terms are nearly international; others are extremely localized, used by a small group of women friends or within a family or other small community. Why do we cloak menstruation in subterfuge? Sometimes out of embarrassment or a sense of decorum, but also, I think, there is the appeal of having an inside joke, speaking a private language, talking about something that is not to be talked about. I am not sure that we are all that shy about menstruation here at the close of the 20th century, but with a modern-day ironic sensibility, it seems funny to pretend to be and to use outlandish codes to discuss something secret in plain view.

The codes fall roughly into four categories: periodicity, personification, allusion to blood, and allusion to emotional state. Of course, many codes overlap two, three, or even all four categories, and some cannot be categorized.

The simplest and most common coding for menstruation relates to its periodicity. Having one’s period is so straightforward that it can hardly be called coding; similarly, women can say it’s that time of the month or the bad, wrong, or funny time of the month. A woman can have her monthlies, her cycle, or her moon-days or moon-time (these last two are fairly new terms, perhaps even new-age). In her 1870s teenage diary, Alice Stone Blackwell (daughter of suffragist Lucy Stone and social reformer Henry Blackwell, who was brother to Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman doctor) abbreviated menstrual period to M.P., as in “M.P. number 3.” In the euphemism-laden 1950s in Wellsville High School in Wellsville, New York (and probably in many other schools as well), girls could cite their monthly excuse to get out of gym class. Right before the menstrual period begins, some women say they are fixin’ to start, abbreviated F.T.S. And I know someone in the 1990s who refers to her Visa bill, which arrives monthly, although she wishes it wouldn’t.

The personification of the period, odd as it may be, is a popular coding. Generally the period takes on the identity of a friend or relative, usually female, who comes for a visit: my friend, my little friend, my aunt, my grandmother, Mother Nature, Miss Rachel, Sophie, or Mary Lou. Description of the visitor can get quite elaborate: my aunt from Redbank or from Redwood City, Reading, or Redfield (with the place name incorporating the color of blood) or my red-haired aunt from the South (incorporating both redness and the idea of the vagina, colloquially down South or down there.) Sometimes the visitors even have names—Dot, Dottie (incorporating the idea of dots of blood), Aunt Rose(incorporating the idea of redness, i.e., blood) or Aunt Flo (i.e., flow, incorporating the idea of the flow of blood). On the Comedy Central cartoon series South Park, Stan Cartman’s Aunt Flo, who happens to be a redhead, comes to visit once a month. While Mrs. Cartman’s monthly visitor is in town, Mr. Cartman sleeps on the couch.

Other visitors might include a midnight visitor (acknowledging the surprise factor), a communist (redness), the chicks, and male visitors such as the Cardinal (redness again) and Charlie, Herbie, Kit, and George, etymology unknown. (These men not only come to visit but become romantically entangled: going steady with George is another term for having one’s period.) One woman I know has developed an entire personality for her monthly visitor, Doris, who drives a brown Chevy Nova and is a large woman with cat-glasses, her appearance similar to women in the old Far Side comics. In bad months, Doris drives up on the lawn, knocks over trees, and generally makes a nuisance of herself.

Codes that refer to blood include the red flag is up (sometimes shortened to just the flag is up or the flag is flying; also sometimes flying Baker, since Baker is the Navy code for B, and the B flag is red), the Red Sea is in, having the painters in, the reds, wearing red shoes, are you a cowboy or an indian? a red-letter day, and riding the red horse. Mrs. E.R. Shepherd, a late 19th-century advice writer, used the term course in For Girls: A Special Physiology (1884), reporting: “I have met numbers of women and some of them young who knew nothing of their coming ‘course’ until they were upon them.” Other blood codes make reference to the gushing or flowing of blood, such as Old Faithful (which also suggests periodicity) or on a streak (the Rolling Stones song “Satisfaction” includes the lyric “Baby, better come back / later next week / ‘cause you see / I’m on a losin’ streak”). And in Act I Scene I of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Gonzalo describes a ship as “leaky as an unstanch’d wench.”

Then there are the codes that stem from unpleasantness, like the curse or the curse of Eve. The origin of this, of course, is Genesis: God curses Eve for eating of the tree of knowledge, saying “in sorrow shalt thou bring forth children,” implying, I suppose, that in sorrow shalt we also have cramps. (Later, Rachel successfully uses a menstruation euphemism to hide stolen goods underneath her on a camel, saying in Genesis 31:35, “Let it not displease my lord that I cannot rise up before thee, for the custom of women is upon me.”) There are the nuisance, G.D.N. (God-damned nuisance), the poorlies, and being unwell or that way. There are also female troubles (a term that can refer to any number of things, menstruation being one of the least troubling).

Of course, the unpleasantness terms have their flip side. At least one woman I know has turned the curse around, calling her period the blessing since it is proof that she is not pregnant. And Anne Frank called menstruation her “sweet secret” despite its “pain and unpleasantness.” (Her father, Otto Frank, edited out these lines for the 1947 Dutch version of the diary.) In the 1950s, Seventeen magazine featured articles on how to cope with special days, a euphemism if I ever heard one. Other pleasant terms include the miracle of menstruation, becoming a woman (for the first period), and, in an early Kotex booklet entitled “Marjorie May’s Twelfth Birthday,” wonderful purification.

(Sanitary supplies have a whole set of euphemisms to themselves, and indeed, the word menstruation does not appear in any Kotex publications until the year 1942, in an ad for a booklet: “Why get all involved trying to explain the facts of menstruation to your little girl . . . when there’s a simple, easy way to do this dreaded task? Let the new booklet ‘As One Girl to Another’ do this job for you!” Other educational pamphlets had suggestive but non-explicit titles like “You’re a Young Lady Now” and “Very Personally Yours.”)